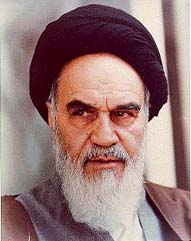

Sentence of Death

As a young seminary teacher, Khomeini was no activist. From the 1920s to the 1940s, he watched passively as Reza Shah, a monarch who took Ataturk as his model, promoted secularization and narrowed clerical powers. Similarly, Khomeini was detached from the great crisis of the 1950s in which Reza Shah's son Mohammed Reza Pahlavi turned to America to save himself from demonstrators on Tehran's streets who were clamoring for democratic reform. Khomeini was then the disciple of Iran's pre-eminent cleric, Ayatullah Mohammed Boroujerdi, a defender of the tradition of clerical deference to established power. But in 1962, after Boroujerdi's death, Khomeini revealed his long-hidden wrath and acquired a substantial following as a sharp-tongued antagonist of the Shah's. Khomeini was clearly at home with populist demagogy. He taunted the Shah for his ties with Israel, warning that the Jews were seeking to take over Iran. He denounced as non-Islamic a bill to grant the vote to women. He called a proposal to permit American servicemen based in Iran to be tried in U.S. military courts "a document for Iran's enslavement." In 1964 he was banished by the Shah to Turkey, then was permitted to relocate in the Shi'ite holy city of An Najaf in Iraq. But the Shah erred in thinking Khomeini would be forgotten. In An Najaf, he received Iranians of every station and sent home tape cassettes of sermons to be peddled in the bazaars. In exile, Khomeini became the acknowledged leader of the opposition. In An Najaf, Khomeini also shaped a revolutionary doctrine. Shi'ism, historically, demanded of the state only that it keep itself open to clerical guidance. Though relations between clergy and state were often tense, they were rarely belligerent. Khomeini, condemning the Shah's servility to America and his secularism, deviated from accepted tenets to attack the regime's legitimacy, calling for a clerical state, which had no Islamic precedent. In late 1978 huge street demonstrations calling for the Shah's abdication ignited the government's implosion. Students, the middle class, bazaar merchants, workers, the army - the pillars of society - successively abandoned the regime. The Shah had nowhere to turn for help but to Washington. Yet the more he did, the more isolated he became. In January 1979 he fled to the West. Two weeks later, Khomeini returned home in triumph. Popularly acclaimed as leader, Khomeini set out to confirm his authority and lay the groundwork for a clerical state. With revolutionary fervor riding high, armed vigilante bands and kangaroo courts made bloody work of the Shah's last partisans. Khomeini canceled an experiment with parliamentarism and ordered an Assembly of Experts to draft an Islamic constitution. Overriding reservations from the Shi'ite hierarchy, the delegates designed a state that Khomeini would command and the clergy would run, enforcing religious law. In November, Khomeini partisans, with anti-American passions still rising, seized the U.S. embassy and held 52 hostages. Over the remaining decade of his life, Khomeini consolidated his rule. Proving himself as ruthless as the Shah had been, he had thousands killed while stamping out a rebellion of the secular left. He stacked the state bureaucracies with faithful clerics and drenched the schools and the media with his personal doctrines. After purging the military and security services, he rebuilt them to ensure their loyalty to the clerical state. Khomeini also launched a campaign to "export" - the term was his - the revolution to surrounding Muslim countries. His provocations of Iraq in 1980 helped start a war that lasted eight years, at the cost of a million lives, and that ended only after America intervened to sink several Iranian warships in the Persian Gulf. Iranians asked whether God had revoked his blessing of the revolution. Khomeini described the defeat as "more deadly than taking poison." To rally his demoralized supporters, he issued the celebrated fatwa condemning to death the writer Salman Rushdie for heresies contained in his novel The Satanic Verses. Though born a Muslim, Rushdie was not a Shi'ite; a British subject, he had no ties to Iran. The fatwa , an audacious claim of authority over Muslims everywhere, was the revolution's ultimate export. Khomeini died a few months later. But the fatwa lived on, a source of bitterness - as he intended it to be - between Iran and the West. |